I’m kidding, of course; I’m not suggesting you should deliberately go out and have open-heart surgery. Unless, of course, your doctor says you need to. But since I’ll be doing it soon, I’m certain it will be all the rage and everyone will want a fashionable chest scar like I’ll have. Since that’s the case, let me tell you how it all came about. I was born with a heart murmur, which I’ve always had to have monitored by my doctor during my regular check-ups.

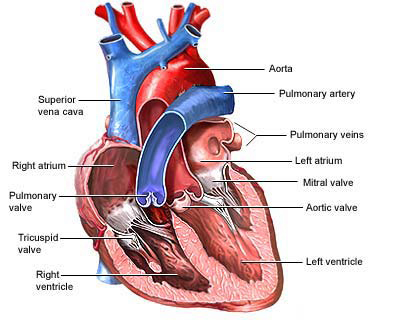

More specifically, I was born with two heart valve defect problems; a pulmonary stenosis, which means my pulmonary valve is too narrow and doesn’t pump blood efficiently, and I also have mitral valve prolapse, which means my mitral valve doesn’t close completely after pumping blood into my left ventrical, and allows blood to flow backwards into my left atrium, causing a whooshing sound or “murmur” when you listen through a stethescope.

The mitral valve (named after a Bishop’s miter) is the “inflow valve” for the main pumping chamber of the heart, the left ventricle. Blood flows from the lungs, where it picks up oxygen, across the open mitral valve and into the left ventricle. When the heart squeezes, the two leaflets of the mitral valve snap shut and prevent blood from backing up to the lungs. Blood is directed out of the heart to the rest of the body through another valve, the aortic valve.

Mitral valve prolapse is fairly common in women; it affects about 15% of the population. It’s less common in men, and men who have it tend to have more problems with the mitral valve as they get older.

Neither of my heart defects affected me much as I was growing up, or at least not that I’ve been aware of before. I had to go to a cardiologist when I was five, which was cool because I got to have an electrocardiogram. They hooked up electrodes to various points on my body that feed into a machine, and sort of like a polygraph test, the needle scrawled across the long strip of paper drawing my heart beat. They gave me the strips of paper and I got to take them to show and tell.

I also got cool chest x-rays, and the doctors were all very nice and showed them to me and pointed out my heart and internal organs hiding in my skeleton on the film, and when you’re five years old, it’s terribly exciting to see your own skeleton.

The only tangible thing that I noticed about my heart murmur was that I had to take antibiotics before I went to the dentist and for any other event where I might get an infection, since an infection can settle in the heart valves and compound the problem.

I’ve always tried to exercise and stay in shape, but I was more of a bookworm than an athlete as a kid, so I don’t really know if my heart condition held me back in activities. I’m not sure if I got tired more easily than other kids or not.

I definitely have noticed a change in the past few years in how tired I get at the gym, and how I get out of breath and short-winded, but I thought I was just more out of shape than I had been in the past, so I would try to work harder. I always thought of my heart murmur as a benign oddity that didn’t affect me much.

My Regular Physical

So today, I’m 36 years old, and about 30 years have passed since I’ve seen a cardiologist. When I went to get my regular physical a couple of weeks ago, my primary care doctor noticed a change in the sound of my heart. She always checks it, and usually it almost seems like an afterthought to the rest of my regular physical, so when she started to pay more attention and listen longer, alarm bells went off in my head.

It turns out that my murmur has gone from a grade 1 to a grade 3 on a scale of 6, meaning it went from a rating of “mild” to “moderate.” It’s possible that this increase in the murmur may be a result of age, or as a result of a possible undetected heart valve infection that occurred when I had appendicitis two summers ago.

My PCP sent me to The Care Group at Methodist Hospital downtown. Initially I went for an echo-cardiogram, which is an ultrasound of the heart, combined with an electrocardiogram. It’s a bit different than a regular ultrasound, because it combines the pictures of the heart with a comparison of the sound and drawings of the heart beat. They look at each of the chambers of the heart and measure some standard points in the size of the chamber and how each of the four valves in the heart open and close. The measurements tell them if a chamber of the heart is enlarged and if the valves are closing completely.

They also use a color doppler detector (much like the TV news weather departments) to view how the blood flows through the heart. So they could see that the red flowing through my mitral valve was good, but the blue color where my blood flowed backwards through the same valve was not so good. It’s really not supposed to do that, and it means my heart pumps much harder to move the same amount of blood around.

My Cardiologist, Dr. Yee

After I went in for the echo, it was several days before I was able to talk to a cardiologist to hear what the results of that were. I went to see Dr. King Yee at the Care Group at Methodist Hospital. He said that the echocardiogram showed that my mitral valve prolapse had worsened, and that my only option was to have open heart surgery to repair the valve. If I don’t, the valve will continue to spread out and the gap when it is “closed” will become larger. In addition, my heart would enlarge from the extra work and become out of shape.

Anther potential problem is that my heart strings could give out. What this means is that the mitral valve is anchored by strings of tissue that act like the cables of the golden gate bridge, or like the lines of a parachute. They keep the valve from being open permanently. It’s possible for these strings to stretch because the valve doesn’t close, and they can also snap, which can cause the valve to fail.

I had no idea that the phrase “tugging at your heart strings” had a real-life source. Interesting.

They do some less invasive procedures for some types of heart valve surgeries, but in my case because the concern was the mitral valve, a valve repair which requires the doctor to have more room to work than a catheter technique would give. So open-heart surgery it is.

While I was in the office to see him, Dr. Yee had me do a stress echo-cardiogram, where they do an echo, then the put you on a treadmill to get your heart rate up as high as possible, then they lay you back down and do another echo while your heart rate is way up. It wasn’t as fun as the last one; it was exhausting. What he was looking for was how my other heart defect was performing, but the pulmonary stenosis seemed to be fine. It appears to have improved from when I was a child, and the doctors feel my pulmonary valve won’t need any repair during the operation.

Transesophageal Echocardiogram

To prepare for the surgery, and to get a really clear picture of what was happening with my heart, my doctors wanted to have me get an Transesphogeal Echocardiogram, or TEE test. It was performed by Dr. James Trippi in the Cardivascular center in Methodist. (Dr. Trippi is well-recognized in Indianapolis for starting Gennesaret Free Clinics in Indianapolis 17 years ago to help homeless and low-income people).

The test is an ultrasound similar to the others, but in this case they stick the ultrasound probe down the patient’s throat and into the esophagus, which sits behind the heart. The resulting ultrasound is a much clearer picture of the heart’s architecture and where the problems lie.

The procedure was more intimidating than I expected; they stick you in a hospital bed and wheel it around from the cath holding area to the cardiovascular area to do the test. Any time you have to put on their clothes and they start moving your bed around, you realize this is a real hospital thing and not a simple “visit the doctor” thing.

My test went really smoothly. It’s a relatively painless procedure and all I had as a result was a slight sore throat, which went away soon after. And they drugs they give you to knock you out are fantastic. I felt really good after the procedure. I apparently asked Doctor Trippi the same question ten times, but I felt good asking it. Fortunately my girlfriend was there to hear all the answers, or I’d be wondering today what the heck we talked about.

They also made me stay and eat dinner, which was pretty cool, except I was still high from the drugs they gave me and ordered odd combos of stuff.

Dr. Trippi also explained that engaging in strenous activities could cause further damage to my mitral valve, and that I should restrict my activities prior to the surgery, because the TEE test showed that my valve’s anchor strings were indeed stretched out, and one of them has snapped. The others are ready to do so, and will if I put pressure on my heart. If one of them does break, I’ll be in the emergency room asking them for surgery as soon as possible.

So — elliptical machine? Bad. Lifting weights heavier than a pound? Bad. Walking up more than a flight of stairs? Bad. Carrying boxes of books? Bad. Opening stuck jars? Bad. Moving groceries into the house? Bad. Anything that involves strain? Bad. Short, casual walks around the neighborhood are okay. Unfortunately the list of restrictions seems to include 40 or 50 things I do every day.

Thank god I didn’t start tearing out the spare room and extra bathroom in my house that I planned to work on this spring. Thank god I went to the doctor for a routine check up so they found this. Thank god I’ve been lazy and used the elevator instead of the stairs at work. I’m pretty fortunate considering all that.

Dr. Daniel Beckman, heart surgeon

Dr. Trippi also gave me the name of the heart surgeon who will be performing my surgery, Dr. Daniel Beckman, whom I met with a few days later. He seems to have a lot written about him out there in the internet ether. Here’s some information about Dr. Beckman. And here’s another bio page on him. Also, here’s some info on some rare procedure that Dr. Beckman is pioneering (not what I need done). Here’s a video [real player required] of Dr. Beckman talking about some rare procedure he’s done on a website about heart surgery. And in this IndyStar article, Dr. Beckman is being interviewed about a surgery he performed. And here’s a mention of him on Channel 6 news’s site about a surgery he performed.

And a couple of medical articles he’s authored or co-authored. One of them is titled “Pain levels experienced with activities after cardiac surgery – Pain Management” — and it’s all about how pain can get in the way of recovery. Yikes! Shouldn’t have read that. And some other paper he wrote, that makes no sense to me at all, but sounds really impressive.

Valve Repair vs. Valve Replacement

Doctor Beckman said that he had looked over all my tests and records, and said that it’s a 90% chance that my surgery will involve only be a valve repair, not a replacement. They will know for sure once they’re in, but he says my chance is good for the repair.

The difference is pretty significant; in a mitral valve repair (called annuloplasty) they would insert a cloth-covered ring to bring the leaflets of my valve together and hold them in place, and possibly repair my heart strings with gore-tex cords.

On the other hand, a valve replacement would require my entire valve be replaced with a mechanical heart valve, which would require me to be on blood-thinners for the rest of my life. Artificial tissue valves will last between 10 and 15 years, placing me at risk of a second operation to replace the valve. The risk of stroke with an artificial mitral valve is significant (approximately 1 percent per year).

Nationwide data suggests that about six percent of patients with a valve replacement do not survive the surgery. But with a mitral valve repair, the chance of survival is about 98 percent. My risk is a bit better, because I’m younger than most open-heart surgery patients.

Several factors influence those numbers. The risk of stroke during and after valve repair is extremely low compared to valve replacement. Artificial valves can cause infection, but infection is unlikely when the patient’s own valve is repaired. Further, repairs are much more likely to last for the rest of my life.

I’m of course hoping for the repair rather than the replacement, because I won’t need to be on anti-coagulant drugs, which means it would still possible to be on The Amazing Race. (Where I would totally milk the “I had open-heart surgery and now I just want to prove what heart patients can do!” vibe for all it’s worth!)

Open-Heart Surgery

If you google the terms “mitral valve repair surgery” you can find some really gory photos of the surgery itself. Don’t do this right after lunch. I speak from experience.

During valve surgery, the doctor makes a large incision in the chest. Blood is circulated outside of the body to add oxygen to it (cardiopulmonary bypass or heart-lung machine). The heart may be cooled to slow or stop the heartbeat; this protects the heart muscle from damage during surgery to repair the heart valve.

At this time they install the cloth covered ring and also do repair of heart strings and any other loose ends.

During all this, I will have a breathing tube in my throat, a drainage tube in my nose, I.V. catheters in my arms and neck, a foley catheter (look that one up yourself), and chest drainage tubes that exit below my breastbone. Sounds like fun, doesn’t it? I will look like a real cyborg, I’m sure.

Recovery

After the surgery, I’ll be in intensive care for several days. During that time I’ll be able to sit in a chair and do some walking around. I will also have to do breathing exercises and cough regularly with a pillow against my chest to prevent pneumonia.

After the surgery, I’ll be in intensive care for several days. During that time I’ll be able to sit in a chair and do some walking around. I will also have to do breathing exercises and cough regularly with a pillow against my chest to prevent pneumonia.

Then I’ll spend several days in a step-down care center, where I’ll regain more of my activities. After five to seven days, I’ll be released from the hospital.

The recovery time is significant and for a little while after I come home I’ll need someone with me to watch me 24 hours a day. The main difficulty in recovering is waiting for my sternum to repair, which is basically the same as waiting for a broken bone to heal. I’ll also need to build up my physical endurance and learn a regular program of exercise.

For the first six to eight weeks I won’t be able to drive, and will be restricted from doing many household chores. (Which is good, because I hate the word “chore” and always feel like I’m on “Little House on the Prairie” when I hear it.)

There is also a possibility of some cognitive decline. That possibility is also less because I’m so young and because I have a higher level of education.

On the bright side, according to this page, I’ll be able to resume fishing after 6 weeks, and firing small caliber pistols after 2 months. Woo hoo!!

Even cooler, I won’t be able to mow the lawn for 3 months. Yeah! I’m hoping to create the first urban jungle in my own yard.

How I Feel About All This

Obviously, this whole thing is very scary, and I’ve gone through a whole range of emotions since I found out about it. I sort of had a feeling from the beginning that there was a real problem, before I even went in for the echocardiogram. I can’t say why I knew that, but it didn’t seem from my regular doctor’s behavior that this was a small problem.

And after talking to Dr. Yee and finding out about the surgery, I was truly scared. The numbers I’m reading about mortality rates after surgery are really really frightening, although I think I have a better situation than most folks who find themselves in my shoes.

Aside from my fear of dying, I’m afraid of how painful the whole experience will be, and I hate the idea of having to have help for everything and not being able to do anything myself. It’s tough right now not being able to do what I normally would.

In all, though, the risks of not having the surgery are huge compared to the risks of having it, so it doesn’t make sense to avoid doing what needs to be done.